Though these book choices are meant to assist with my teaching, they are also chosen because they are ones I hope to find personally enlightening. As aforementioned, having previously felt ill-equipped to make recommendations to my grade 11 university-level students, I have been centering on biographies for the moment. I relate to all selections thus far in some way.

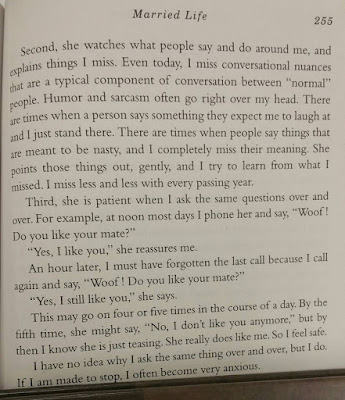

Look Me in the Eye: My Life with Asperger's by John Elder Robison is incredibly endearing. I picked it up as solace for myself on an off-day - intending to read it in bits and pieces - and could not put it down for long. I recommended it to my colleagues, only 70 pages in, and one said he had already read it twice, and had intended to pass it along for me to borrow. (This illustrates both: (a) This book is good, and (b) I work with good people.)

Robison's biography is equal parts heartwarming, heartbreaking, and hilarious. Geoff summed the latter up well when he said: "It's not often I hear you laugh aloud while reading." I had to then read him parts of the narrative - and he laughed, too.

I'll leave with you with some insights that resonated the most with me:

"To this day when I speak, I find visual input to be distracting. When I was younger, if I saw something interesting I might begin to watch it and stop speaking entirely. As a grown-up, I don't usually come to a complete stop, but I may still pause if something catches my eye. That's why I usually look at somewhere neutral - at the ground, or off into the distance - when I'm talking to someone. Because speaking while watching things has always been difficult for me, learning to drive a car and talk at the same time was a tough one, but I mastered it." (3)

"It's been many years since I could fit into a space that small. I liked squeezing myself up tight in a tiny ball when I was little, hiding where no one could see me. I still like the feeling of lying under things and having them press on me. Today, when I lie on the bed I'll pile the pillows on top of me because it feels better than a sheet." (16)

"I don't recall any grown-up ever trying to figure out why I was staring. I might have been able to tell them if they had asked. Sometimes I was thinking of other things and just gazing their way absentmindedly. Other times I was watching them intently, trying to figure out their behaviour." (89)

"By 1988, I had moved through two more jobs, and I had swallowed all I could take of the corporate world. I had come to accept what my annual performance reviews said. I was not a team player. I had trouble communicating with people. I was inconsiderate. I was rude. I was smart and creative, yes, but I was a misfit. I was thoroughly sick of all the criticism. I was sick of life. Literally. I had come down with asthma, and attacks were sending me to the emergency room every few months. I hated to get up and face another day at work. I knew what I needed to do. I needed to stop forcing myself to fit into something I could never be a part of. A big company. A group. A team. When I was five, I had wanted more than anything to be part of the team. When I was a little older, I had tried out for Little League, but no one had picked me. I never tried out for a team after that. Maybe those rejections were still with me, twenty years later." (205)

"Scientists have studied 'brain plasticity,' the ability of the brain to reorganize neural pathways based on new experiences. It appears that different types of plasticity are dominant at different ages. Looking back on my childhood, I think the ages of four to seven were critical for my social development. That was when I cried and hurt because I could not make friends. At those times, I could have withdrawn further from people so that I would not get hurt, but I didn't. Fortunately, I had enough satisfactory exchanges with intelligent grown-ups - my family and their friends at college - to keep me wanting to interact. I can easily imagine a child who did not have any satisfying exchanges withdrawing from people entirely. And a kid who withdrew at age five might be very hard to coax out later. I also believe considerable rewiring took place in my own brain in my thirties and even later." (209)

"Many descriptions of autism and Asperger's describe people like me as 'not wanting contact with others' or 'preferring to play alone.' I can't speak for other kids, but I'd like to be very clear about my own feelings: I did not ever want to be alone. And all those child psychologists who said: 'John prefers to play by himself' were dead wrong. I played by myself because I was a failure at playing with others. I was alone as a result of my own limitations, and being alone was one of the bitterest disappointments of my young life. The sting of those early failures followed me long into adulthood, even after I learned about Asperger's." (211)

"I didn't have to know everything. Other people could tell me the answers. I didn't have to notice everything. My friends would look out for me. Suddenly, I had a revelation: This is what life is like for normal people." (263)

"One last thing: I may look or act pretty strange sometimes, but deep down I just want to be loved and understood for who and what I am. I want to be accepted as part of society, not an outcast or outsider. I don't want to be a genius or a freak or something on display. I wish for empathy and compassion from those around me, and I appreciate sincerity, clarity and logicality in other people. I believe most people - autistic or not - share this wish." (288)